| Ford Model T | |

|---|---|

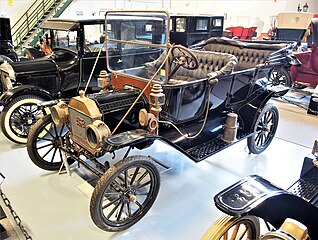

1925 Ford Model T Touring Car

|

|

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Ford Motor Company |

| Production | 1908–1927 |

| Assembly |

List |

| Designer | Childe Harold Wills, main-engineer Joseph A. Galamb and Eugene Farkas |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Economy car[13] |

| Body style |

List |

| Layout | FMR layout |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | 177 C.I.D. (2.9 L) 20 hp I4 |

| Transmission | 2-speed planetary gear |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 100.0 in (2,540 mm) |

| Length | 134 in (3,404 mm) |

| Width | 1,676 mm (66.0 in) (1912 roadster)[14] |

| Height | 1,860 mm (73.2 in) (1912 roadster)[14] |

| Curb weight | 1,200–1,650 lb (540–750 kg) |

| Chronology | |

| Predecessor | Ford Model N (1906–1908) |

| Successor | Ford Model A (1927–31) |

The Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by the Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927.[15] It is generally regarded as the first mass-affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans.[16] The relatively low price was partly the result of Ford’s efficient fabrication, including assembly line production instead of individual handcrafting.[17] It was mainly designed by three engineers, Joseph A. Galamb (the main-engineer),[18][19] Eugene Farkas, and Childe Harold Wills. The Model T was colloquially known as the “Tin Lizzie“, “Leaping Lena” or “flivver“.[20][21]

The Ford Model T was named the most influential car of the 20th century in the 1999 Car of the Century competition, ahead of the BMC Mini, Citroën DS, and Volkswagen Beetle.[22] Ford’s Model T was successful not only because it provided inexpensive transportation on a massive scale, but also because the car signified innovation for the rising middle class and became a powerful symbol of the United States’ age of modernization.[23] With 15 million sold, it was the most sold car in history before being surpassed by the Volkswagen Beetle in 1972,[24] and still stood eighth on the top-ten list, as of 2012.[25]

Although automobiles had been produced from the 1880s, until the Model T was introduced in 1908, they were mostly scarce, expensive, and often unreliable. Positioned as reliable, easily maintained, mass-market transportation, the Model T was a great success. In a matter of days after the release, 15,000 orders had been placed.[26] The first production Model T was built on August 12, 1908,[27] and left the factory on September 27, 1908, at the Ford Piquette Avenue Plant in Detroit, Michigan. On May 26, 1927, Henry Ford watched the 15 millionth Model T Ford roll off the assembly line at his factory in Highland Park, Michigan.[28]

Henry Ford conceived a series of cars between the founding of the company in 1903 and the introduction of the Model T. Ford named his first car the Model A and proceeded through the alphabet up through the Model T, twenty models in all. Not all the models went into production. The production model immediately before the Model T was the Model S,[29] an upgraded version of the company’s largest success to that point, the Model N. The follow-up to the Model T was another Ford Model A, rather than the “Model U”. The company publicity said this was because the new car was such a departure from the old that Ford wanted to start all over again with the letter A.

The Model T was Ford’s first automobile mass-produced on moving assembly lines with completely interchangeable parts, marketed to the middle class.[30] Henry Ford said of the vehicle:

I will build a motor car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family, but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one – and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.[31]

Although credit for the development of the assembly line belongs to Ransom E. Olds, with the first mass-produced automobile, the Oldsmobile Curved Dash, having begun in 1901, the tremendous advances in the efficiency of the system over the life of the Model T can be credited almost entirely to Ford and his engineers.[32]

The Model T was designed by Childe Harold Wills, and Hungarian immigrants Joseph A. Galamb (main engineer)[18][33] and Eugene Farkas.[34] Henry Love, C. J. Smith, Gus Degner and Peter E. Martin were also part of the team,[35] as were Galamb’s fellow Hungarian immigrants Gyula Hartenberger and Károly Balogh.[18] Production of the Model T began in the third quarter of 1908.[36] Collectors today sometimes classify Model Ts by build years and refer to these as “model years,” thus labeling the first Model Ts as 1909 models. This is a retroactive classification scheme; the concept of model years as understood today did not exist at the time. Even though design revisions occurred during the car’s two decades of production, the company gave no particular name to any of the revised designs; all of them were called simply “Model T”.

The Model T has a front-mounted 177-cubic-inch (2.9 L) inline four-cylinder engine, producing 20 hp (15 kW), for a top speed of 42 mph (68 km/h).[37] According to Ford Motor Company, the Model T had fuel economy on the order of 13–21 mpg‑US (16–25 mpg‑imp; 18–11 L/100 km).[38] The engine was capable of running on gasoline, kerosene, or ethanol,[39][40] although the decreasing cost of gasoline and the later introduction of Prohibition made ethanol an impractical fuel for most users. The engines of the first 2,447 units were cooled with water pumps; the engines of unit 2,448 and onward, with a few exceptions prior to around unit 2,500, were cooled by thermosiphon action.[41]

The ignition system used in the Model T was an unusual one, with a low-voltage magneto incorporated in the flywheel, supplying alternating current to trembler coils to drive the spark plugs. This was closer to that used for stationary gas engines than the expensive high-voltage ignition magnetos that were used on some other cars. This ignition also made the Model T more flexible as to the quality or type of fuel it used. The system did not need a starting battery, since proper hand-cranking would generate enough current for starting. Electric lighting powered by the magneto was adopted in 1915, replacing acetylene gas flame lamp and oil lamps, but electric starting was not offered until 1919.[42]

The Model T engine was produced for replacement needs as well as stationary and marine applications until 1941, well after production of the Model T had ended.

The Fordson Model F tractor engine, that was designed about a decade later, was very similar to, but larger than, the Model T engine.[43]

The Model T is a rear-wheel drive vehicle. Its transmission is a planetary gear type known (at the time) as “three speed”. In today’s terms it is considered a two-speed, because one of the three speeds is reverse.

The Model T’s transmission is controlled with three floor-mounted pedals, a revolutionary feature for its time,[44] and a lever mounted to the road side of the driver’s seat. The throttle is controlled with a lever on the steering wheel. The left-hand pedal is used to engage the transmission. With the floor lever in either the mid position or fully forward and the pedal pressed and held forward, the car enters low gear. When held in an intermediate position, the car is in neutral. If the left pedal is released, the Model T enters high gear, but only when the lever is fully forward – in any other position, the pedal only moves up as far as the central neutral position. This allows the car to be held in neutral while the driver cranks the engine by hand. The car can thus cruise without the driver having to press any of the pedals.

In the first 800 units, reverse is engaged with a lever; all units after that use the central pedal, which is used to engage reverse gear when the car is in neutral.[41] The right-hand pedal operates the transmission brake – there are no brakes on the wheels. The floor lever also controls the parking brake, which is activated by pulling the lever all the way back. This doubles as an emergency brake.

Although it was uncommon, the drive bands could fall out of adjustment, allowing the car to creep, particularly when cold, adding another hazard to attempting to start the car: a person cranking the engine could be forced backward while still holding the crank as the car crept forward, although it was nominally in neutral. As the car utilizes a wet clutch, this condition could also occur in cold weather, when the thickened oil prevents the clutch discs from slipping freely. Power reaches the differential through a single universal joint attached to a torque tube which drives the rear axle; some models (typically trucks, but available for cars, as well) could be equipped with an optional two-speed rear Ruckstell axle, shifted by a floor-mounted lever which provides an underdrive gear for easier hill climbing.

The heavy-duty Model TT truck chassis came with a special worm gear rear differential with lower gearing than the normal car and truck, giving more pulling power but a lower top speed (the frame is also stronger; the cab and engine are the same). A Model TT is easily identifiable by the cylindrical housing for the worm-drive over the axle differential. All gears are vanadium steel running in an oil bath.

Two main types of band lining material were used:[45]

- Cotton – Cotton woven linings were the original type fitted and specified by Ford. Generally, the cotton lining is “kinder” to the drum surface, with damage to the drum caused only by the retaining rivets scoring the drum surface. Although this in itself did not pose a problem, a dragging band resulting from improper adjustment caused overheating of the transmission and engine, diminished power, and – in the case of cotton linings – rapid destruction of the band lining.

- Wood – Wooden linings were originally offered as a “longer life” accessory part during the life of the Model T. They were a single piece of steam-bent wood and metal wire, fitted to the normal Model T transmission band.[46] These bands give a very different feel to the pedals, with much more of a “bite” feel. The sensation is of a definite “grip” of the drum and seemed to noticeably increase the feel, in particular of the brake drum.

During the Model T’s production run, particularly after 1916, more than 30 manufacturers offered auxiliary transmissions or drives to substitute for, or enhance, the Model T’s drivetrain gears. Some offered overdrive for greater speed and efficiency, while others offered underdrives for more torque (often incorrectly described as “power”) to enable hauling or pulling greater loads. Among the most noted were the Ruckstell two-speed rear axle, and transmissions by Muncie, Warford, and Jumbo.[47][48]

Aftermarket transmissions generally fit one of four categories:

- Replacement transmission – usually a sliding gear/selective transmission, intended as a direct replacement for Ford’s planetary-gear transmission.[48]

- Front-mounted auxiliary transmission – designed to fit between the engine and Ford’s transmission, to add additional gear ratios.[48]

- Rear-mounted auxiliary transmission – mounted at the rear axle housing, and attached between it and the driveshaft, to add additional gear ratios.[48]

- Multi-speed axle – designed to fit inside the differential’s housing, to add additional gear ratios.[48]

Murray Fahnestock, a Ford expert in the era of the Model T, particularly advised the use of auxiliary transmissions for the enclosed Model T’s, such as the Ford Sedan and Coupelet, for three reasons: their greater weight put more strain on the drivetrain and engine, which auxiliary transmissions could smooth out; their bodies acted as sounding boards, echoing engine noise and vibration at higher engine speeds, which could be lessened with intermediate gears; and owners of the enclosed cars spent more to buy them, and thus likely had more money with which to enhance them.[47]

He also noted that auxiliary transmissions were valuable for Ford Ton-Trucks in commercial use, allowing for driving speeds to vary with their widely variable loads – particularly when returning empty – possibly saving as much as 50% of returning drive time.[47]

Model T suspension employed a transversely mounted semi-elliptical spring for each of the front and rear beam axles which allowed a great deal of wheel movement to cope with the dirt roads of the time.

The front axle was drop forged as a single piece of vanadium steel. Ford twisted many axles through eight full rotations (2880 degrees) and sent them to dealers to be put on display to demonstrate its superiority.

The Model T did not have a modern service brake. The right foot pedal applied a band around a drum in the transmission, thus stopping the rear wheels from turning. The previously mentioned parking brake lever operated band brakes acting on the inside of the rear brake drums, which were an integral part of the rear wheel hubs. Optional brakes that acted on the outside of the brake drums were available from aftermarket suppliers.

Wheels were wooden artillery wheels, with steel welded-spoke wheels available in 1926 and 1927.

Tires were pneumatic clincher type, 30 in (762 mm) in diameter, 3.5 in (89 mm) wide in the rear, 3 in (76 mm) in the front. Clinchers needed much higher pressure than today’s tires, typically 60 psi (410 kPa), to prevent them from leaving the rim at speed. Flat tires were a common problem.

Balloon tires became available in 1925. They were 21 in × 4.5 in (530 mm × 110 mm) all around. Balloon tires were closer in design to today’s tires, with steel wires reinforcing the tire bead, making lower pressure possible – typically 35 psi (240 kPa) – giving a softer ride. The steering gear ratio was changed from 4:1 to 5:1 with the introduction of balloon tires.[49] The old nomenclature for tire size changed from measuring the outer diameter to measuring the rim diameter so 21 in (530 mm) (rim diameter) × 4.5 in (110 mm) (tire width) wheels has about the same outer diameter as 30 in (760 mm) clincher tires. All tires in this time period used an inner tube to hold the pressurized air; tubeless tires were not generally in use until much later.

Wheelbase is 100 in (254 cm) and standard track width was 56 in (142 cm) – 60 in (152 cm) track could be obtained on special order, “for Southern roads”, identical to the pre-Civil War track gauge for many railroads in the former Confederacy. The standard 56-inch track being very near the 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (143.5 cm) inch standard railroad track gauge, meant that Model Ts could be and frequently were, fitted with flanged wheels and used as motorized railway vehicles or “speeders”. The availability of a 60 in (152 cm) version meant the same could be done on the few remaining Southern 5 ft (152 cm) railways – these being the only nonstandard lines remaining, except for a few narrow-gauge lines of various sizes. Although a Model T could be adapted to run on track as narrow as 2 ft (61 cm) gauge (Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington RR, Maine has one), this was a more complex alteration.

By 1918, half of all the cars in the U.S. were Model Ts. In his autobiography, Ford reported that in 1909 he told his management team, “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black.”[50]

However, in the first years of production from 1908 to 1913, the Model T was not available in black,[51] but rather only in gray, green, blue, and red. Green was available for the touring cars, town cars, coupes, and Landaulets. Gray was available for the town cars only and red only for the touring cars. By 1912, all cars were being painted midnight blue with black fenders. Only in 1914 was the “any color so long as it is black” policy finally implemented.

It is often stated Ford suggested the use of black from 1914 to 1925 due to the low cost, durability, and faster drying time of black paint in that era. There is no evidence that black dried any faster than any other dark varnishes used at the time for painting,[52] but carbon black pigment was indeed one of the cheapest (if not the cheapest) available, and dark color of gilsonite, a form of bitumen making cheap metal paints of the time durable, limited the (final) color options to dark shades of maroon, blue, green or black.[53] At that period Ford used two similar types of the so-called Japan black paint, one as a basic coat applied directly to the metal and another as a final finish.

Paint choices in the American automotive industry, as well as in others (including locomotives, furniture, bicycles, and the rapidly expanding field of electrical appliances), were shaped by the development of the chemical industry. These included the disruption of dye sources during World War I and the advent, by the mid-1920s, of new nitrocellulose lacquers that were faster-drying and more scratch-resistant and obviated the need for multiple coats.[54]: 261–301 Understanding the choice of paints for the Model T era and the years immediately following requires an understanding of the contemporaneous chemical industry.[54]

During the lifetime production of the Model T, over 30 types of black paint were used on various parts of the car.[51] These were formulated to satisfy the different means of applying the paint to the various parts, and had distinct drying times, depending on the part, paint, and method of drying.

- bodies

-

1910 Model T, photographed in Salt Lake City

-

1917 Model T

-

1915 Model T Speedster

-

1925 Ford “New Model” T Tudor sedan

Although Ford classified the Model T with a single letter designation throughout its entire life and made no distinction by model years, enough significant changes to the body were made over the production life that the car may be classified into several style generations. The most immediately visible and identifiable changes were in the hood and cowl areas, although many other modifications were made to the vehicle.

- 1909–1914 – Characterized by a nearly straight, five-sided hood, with a flat top containing a center hinge and two side sloping sections containing the folding hinges. The firewall is flat from the windshield down with no distinct cowl. For these years, acetylene gas flame headlights were used because the flame is resistant to wind and rain. Thick concave mirrors combined with magnifying lenses projected the acetylene flame light. The fuel tank is placed under the front seat.

- 1915–1916 – The hood design is nearly the same five-sided design with the only obvious change being the addition of louvers to the vertical sides. A significant change to the cowl area occurred with the windshield relocated significantly behind the firewall and joined with a compound-contoured cowl panel. In these years electric headlights replaced carbide headlights.

- 1917–1923 – The hood design was changed to a tapered design with a curved top. The folding hinges were now located at the joint between the flat sides and the curved top. This is sometimes referred to as the “low hood” to distinguish it from the later hoods. The back edge of the hood now met the front edge of the cowl panel so that no part of the flat firewall was visible outside of the hood. This design was used the longest and during the highest production years, accounting for about half of the total number of Model Ts built.

- 1923–1925 – This change was made during the 1923 calendar year, so models built earlier in the year have the older design, while later vehicles have the newer design. The taper of the hood was increased and the rear section at the firewall is about an inch taller and several inches wider than the previous design. While this is a relatively minor change, the parts between the third and fourth generations are not interchangeable.

- 1926–1927 – This design change made the greatest difference in the appearance of the car. The hood was again enlarged, with the cowl panel no longer a compound curve and blended much more with the line of the hood. The distance between the firewall and the windshield was also increased significantly. This style is sometimes referred to as the “high hood”.

The styling on the last “generation” was a preview for the following Model A, but the two models are visually quite different, as the body on the A is much wider and has curved doors as opposed to the flat doors on the T.

- Diverse applications

-

A Model T homemade tractor pulling a plow

-

Pullford auto-to-tractor conversion advertisement, 1918

-

The American LaFrance company modified more than 900 Ford Model Ts to serve firefighters.

When the Model T was designed and introduced, the infrastructure of the world was quite different from today’s. Pavement was a rarity except for sidewalks and a few big-city streets. (The meaning of the term “pavement” as opposed to “sidewalk” comes from that era, when streets and roads were generally dirt and sidewalks were a paved way to walk along them.) Agriculture was the occupation of many people. Power tools were scarce outside factories, as were power sources for them; electrification, like pavement, was found usually only in larger towns. Rural electrification and motorized mechanization were embryonic in some regions and nonexistent in most. Henry Ford oversaw the requirements and design of the Model T based on contemporary realities. Consequently, the Model T was (intentionally) almost as much a tractor and portable engine as it was an automobile. It has always been well regarded for its all-terrain abilities and ruggedness. It could travel a rocky, muddy farm lane, cross a shallow stream, climb a steep hill, and be parked on the other side to have one of its wheels removed and a pulley fastened to the hub for a flat belt to drive a bucksaw, thresher, silo blower, conveyor for filling corn cribs or haylofts, baler, water pump, electrical generator, and many other applications. One unique application of the Model T was shown in the October 1922 issue of Fordson Farmer magazine. It showed a minister who had transformed his Model T into a mobile church, complete with small organ.[55]

During this era, entire automobiles (including thousands of Model Ts) were hacked apart by their owners and reconfigured into custom machinery permanently dedicated to a purpose, such as homemade tractors and ice saws.[56] Dozens of aftermarket companies sold prefab kits to facilitate the T’s conversion from car to tractor.[57] The Model T had been around for a decade before the Fordson tractor became available (1917–18), and many Ts had been converted for field use. (For example, Harry Ferguson, later famous for his hitches and tractors, worked on Eros Model T tractor conversions before he worked with Fordsons and others.) During the next decade, Model T tractor conversion kits were harder to sell, as the Fordson and then the Farmall (1924), as well as other light and affordable tractors, served the farm market. But during the Depression (1930s), Model T tractor conversion kits had a resurgence, because by then used Model Ts and junkyard parts for them were plentiful and cheap.[58]

Like many popular car engines of the era, the Model T engine was also used on home-built aircraft (such as the Pietenpol Sky Scout) and motorboats.

An armored-car variant (called the “FT-B”) was developed in Poland in 1920 due to the high demand during the Polish-Soviet war in 1920.

Many Model Ts were converted into vehicles that could travel across heavy snows with kits on the rear wheels (sometimes with an extra pair of rear-mounted wheels and two sets of continuous track to mount on the now-tandemed rear wheels, essentially making it a half-track) and skis replacing the front wheels. They were popular for rural mail delivery for a time. The common name for these conversions of cars and small trucks was “snowflyers”. These vehicles were extremely popular in the northern reaches of Canada, where factories were set up to produce them.[59]

A number of companies built Model T–based railcars.[60] In The Great Railway Bazaar, Paul Theroux mentions a rail journey in India on such a railcar. The New Zealand Railways Department’s RM class included a few.

The American LaFrance company modified more than 900 Model Ts for use in firefighting, adding tanks, hoses, tools and a bell.[61] Model T fire engines were in service in North America, Europe, and Australia.[62][61] A 1919 Model T equipped to fight chemical fires has been restored and is on display at the North Charleston Fire Museum in South Carolina.[63]

The knowledge and skills needed by a factory worker were reduced to 84 areas. When introduced, the T used the building methods typical at the time, assembly by hand, and production was small. The Ford Piquette Avenue Plant could not keep up with demand for the Model T, and only 11 cars were built there during the first full month of production. More and more machines were used to reduce the complexity within the 84 defined areas. In 1910, after assembling nearly 12,000 Model Ts, Henry Ford moved the company to the new Highland Park complex. During this time the Model T production system (including the supply chain) transitioned into an iconic example of assembly-line production.[30][64] In subsequent decades it would also come to be viewed as the classic example of the rigid, first-generation version of assembly line production, as opposed to flexible mass production[30] of higher quality products.[64]

As a result, Ford’s cars came off the line in three-minute intervals, much faster than previous methods, reducing production time from 12+1⁄2 hours before to 93 minutes by 1914, while using less manpower.[65] In 1914, Ford produced more cars than all other automakers combined. The Model T was a great commercial success, and by the time Ford made its 10 millionth car, half of all cars in the world were Fords. It was so successful Ford did not purchase any advertising between 1917 and 1923; instead, the Model T became so famous, people considered it a norm. More than 15 million Model Ts were manufactured in all, reaching a rate of 9,000 to 10,000 cars a day in 1925, or 2 million annually,[66][67][68] more than any other model of its day, at a price of just $260 ($4,339 today). Total Model T production was finally surpassed by the Volkswagen Beetle on February 17, 1972, while the Ford F-Series (itself directly descended from the Model T roadster pickup) has surpassed the Model T as Ford’s all-time best-selling model.

Henry Ford’s ideological approach to Model T design was one of getting it right and then keeping it the same; he believed the Model T was all the car a person would, or could, ever need. As other companies offered comfort and styling advantages, at competitive prices, the Model T lost market share and became barely profitable.[64] Design changes were not as few as the public perceived, but the idea of an unchanging model was kept intact. Eventually, on May 26, 1927, Ford Motor Company ceased US production[69][70][71] and began the changeovers required to produce the Model A.[72] Some of the other Model T factories in the world continued for a short while,[73] with the final Model T produced at the Cork, Ireland plant in December 1928.[74]

Model T engines continued to be produced until August 4, 1941. Almost 170,000 were built after car production stopped, as replacement engines were required to service the many existing vehicles. Racers and enthusiasts, forerunners of modern hot rodders, used the Model Ts’ blocks to build popular and cheap racing engines, including Cragar, Navarro, and, famously, the Frontenacs (“Fronty Fords”)[70] of the Chevrolet brothers, among many others.

The Model T employed some advanced technology, for example, its use of vanadium steel alloy. Its durability was phenomenal, and some Model Ts and their parts are in running order over a century later. Although Henry Ford resisted some kinds of change, he always championed the advancement of materials engineering, and often mechanical engineering and industrial engineering.

In 2002, Ford built a final batch of six Model Ts as part of their 2003 centenary celebrations. These cars were assembled from remaining new components and other parts produced from the original drawings. The last of the six was used for publicity purposes in the UK.[citation needed]

Although Ford no longer manufactures parts for the Model T, many parts are still manufactured through private companies as replicas to service the thousands of Model Ts still in operation today.

On May 26, 1927, Henry Ford and his son Edsel drove the 15-millionth Model T out of the factory.[28] This marked the famous automobile’s official last day of production at the main factory.

The moving assembly line system, which started on October 7, 1913, allowed Ford to reduce the price of his cars.[75] As he continued to fine-tune the system, Ford was able to keep reducing costs significantly.[76] As volume increased, he was able to also lower the prices due to some of the fixed costs being spread over a larger number of vehicles[64] as large supply chain investments increased assets per vehicle. Other factors reduced the price such as material costs and design changes.[64] As Ford had market dominance in North America during the 1910s, other competitors reduced their prices to stay competitive, while offering features that were not available on the Model T such as a wide choice of colors, body styles and interior appearance and choices, and competitors also benefited from the reduced costs of raw materials and infrastructure benefits to supply chain and ancillary manufacturing businesses.

In 1909, the cost of the Runabout started at $825 (equivalent to $26,870 in 2022). By 1925 it had been lowered to $260 (equivalent to $4,340 in 2022).

The figures below are US production numbers compiled by R. E. Houston, Ford Production Department, August 3, 1927. The figures between 1909 and 1920 are for Ford’s fiscal year. From 1909 to 1913, the fiscal year was from October 1 to September 30 the following calendar year with the year number being the year in which it ended. For the 1914 fiscal year, the year was October 1, 1913, through July 31, 1914. Starting in August 1914, and through the end of the Model T era, the fiscal year was August 1 through July 31. Beginning with January 1920, the figures are for the calendar year.

- Model T chronology

-

1909 touring (a very early example with two-pedal, two-lever control)

-

1909 roadster

-

1909 Tourabout (like the touring, but without rear doors)

-

1911 touring

-

1911 Torpedo Runabout

-

1911 Open Runabout

-

1912 touring

-

1912 commercial roadster

-

1912 Torpedo Runabout

-

1912 delivery car

-

1913 Touring

-

1913 Runabout

-

1914 touring

-

1914 Runabout

-

1915 Runabout – curved cowl panel added

-

1916 touring

-

1917 Runabout – begin curved hood to match cowl panel

-

1919 Runabout

-

1920 touring

-

1921 Ford Model T

-

1921 touring

-

1922 Runabout

-

1922 flatbed truck

-

1923 Ford Model T depot hack

-

1923 Runabout (early ’23 model)

-

1924 touring – begin higher hood and slightly shorter cowl panel – late-1923 models were similar

-

1924–1925 Runabout

-

1925 touring – with the balloon tires and split rims, optional extras of the period

-

1925 touring

-

1926 Runabout – begin higher hood and longer cowl panel

-

1927 Runabout

-

1927 touring – last Ford Model T built at Highland Park Ford Plant

-

BETWEEN

DENMARK

AND

DETROIT

Aarhus University Press

Ford Motor Company A/S and

the Transformation of Fordism 1919–1966

LARS K. CHRISTENSENBETWEEN DENMARK AND DETROIT

A breath of air from the USA

was clearly felt in the South Port

yesterday morning, when the solemn

inauguration of the Ford factory

was about to take place

Social-Demokraten, 16 November 1924

Dedicated to the memory of Knud Erik Christensen

Ford Motor Company A/S and

the Transformation of Fordism 1919–1966

BETWEEN

DENMARK

AND

DETROIT

Aarhus University Press

LARS K. CHRISTENSEN

4 Between Denmark and Detroit

© Lars K. Christensen and Aarhus University Press 2021

Cover illustration: Showroom in Copenhagen established by Ford in 1934.

Unknown photographer. Ford Motor Company A/S gennem 25 Aar

Layout, typesetting, and cover: Carl-H.K. Zakrisson and Tod Alan Spoerl

Publishing editors: Søren Hein Rasmussen and Karina Bell Ottosen

This book is typeset in Kabel and dtl Documenta

E-book production by Narayana Press, Denmark

isbn 9788771848373 (e-pdf )

Aarhus University Press

aarhusuniversitypress.dk

Published with the financial support of Farumgaard-Fonden, The Foundation

for the benefit of the National Museum of Denmark’s Danish collections

after 1660, the Hielmstierne-Rosencroneske Foundation, Konsul George Jorck

og Hustru Emma Jorck’s Fond, and the Otto Moensted Foundation

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose

of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored

in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the

prior permission of the publisher

International distributors:

Oxbow Books Ltd., oxbowbooks.com

ISD, isdistribution.com

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have

been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will honour valid claims as

if clearance had been obtained beforehand.Content

Acknowledgements 7

Introduction 11

The Creation of Fordism 17

Fordism Made in Detroit 18

Conceptualising Fordism 33

1919–1928 Pioneering Years 43

Making Cars in Copenhagen 43

Model T for Export 65

By Proxy from Detroit 77

Defying Henry’s Plans 96

In the Eye of the Public 125

1928–1940 Time for Change 141

Volume and Diversity 141

A Broader Portfolio 151

Under English Lords 158

Slowly Towards Normal 169

On the Road to Modernity 178

1940–1945 Interregnum 195

Keeping Things Going 195

Unfamiliar Products 199

Dealing with Germany 201

Growing Impatience 204

Dilemmas 206

51945–1958 New Expectations 213

Working the Same Way, but Faster 213

Fewer Markets, More Demand 217

This Is an American Company 222

New Hopes 229

Cars for Freedom 246

1958–1966 Expansion and Decline 257

Just Not Enough 257

The Germans Are Coming 262

American Leadership 266

In the Mainstream 271

Fireworks Before Closure 276

The Transformation of Fordism 281

A Case of Hybridisation 281

Labour and Fordism 298

Fordism as Americanism 310

Appendix 323

Fordism in Literature 323

Types and Origin of Primary Sources 327

Statistics: Long-Term Trends 330

List of Tables and Figures 334

Danish Names of Associations and Institutions 336

Notes 339

References 363

Source material, photographs, and film 363

Newspapers, periodicals, and handbooks 365

Books and articles 366

7

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

During my research for this book, I have spent countless hours in the

reading rooms of archives and libraries. Without the help I have had

from the knowledgeable staff of those institutions, my work would

never had been finished. They are all listed in the Appendix, but I

would especially like to thank the present and former staff of the

Library and Archive of the Workers Museum. Not only is this a formidable collection of material related to labour history, but it is also

being managed with great dedication and professionalism.

Another indispensable repository of source material has been the

historical archive of Ford Motor Company A/S. I am very grateful to

the company for showing me the confidence of letting me use their

archive. And I would like to thank Lene Dahlquist, Head of Communication and Public Affairs, for always finding the time to be helpful and hospitable during my many visits. My thanks also go to the

other members of the staff and management of Ford Motor Company A/S, whom I have had the chance to meet along the way.

During my research I came into contact with Ben Larsen, son of Orla

Larsen who was employed at Ford Motor Company A/S almost from

its start, and for more than forty years thereafter, as part of the management. Ben granted me access to his father’s private collection of

notes, clippings, and photographs, for which I am very grateful.

After working on the research for this book for almost ten years,

the list of people with whom I have had the chance to discuss aspects

of it has grown very long. It is impossible for me to list them all. But

at least two deserve special mentioning: Kenn Tarbensen, Senior

Researcher at the Danish National Archives, with whom I have had

several fruitful discussions along the way; and Per Boje, professor

emeritus at the University of Southern Denmark, who has provided

8

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

between denmark and detroit

me with very useful comments on the manuscript. Others, who have

been kind enough to provide me with specific bits of information,

have been mentioned in the notes where appropriate.

I have also had the privilege of being part of several forums, in

which I have had the chance to present my research and get feedback

and ideas for further work. These include my former colleagues at the

National Museum, the Danish Society for Labour History (SFAH)

and, last but not least, the Working Group on Factory History within the European Labour History Network. Without inspiration from

so many people, not only would my work have been tedious, but the

result would have suffered in quality. But in the end, the responsibility for any errors and omissions in the following text is of course mine

alone.

The staff at Aarhus University press have been of great help in

bringing this project from the stage of a manuscript to a finished book.

During the long period of time I have been working on this project, my family and friends have had to endure my lengthy talks about

the peculiarities of Fordism ever so often. I am thankful that they are

still here and still my friends. I especially want to express my gratitude to the one who has endured more than anyone in this respect,

my wife Jytte Christensen, for her patience and support.

Finally, the publication of this book would not have been possible

without generous financial support from a number of foundations.

I am very grateful for the contributions received from FarumgaardFonden, the Otto Moensted Foundation, Konsul George Jorck og

Hustru Emma Jorck’s Fond, the Hielmstierne-Rosencroneske Foundation and The Foundation for the benefit of the National Museum

of Denmark’s Danish collections after 1660. The Farumgaard Foundation has furthermore supported my research trip to the Benson

Ford Research Centre in Dearborn, Detroit.

When I grew up, my father worked as an industrial spray painter.

He had done his apprenticeship as a house painter in the 1950s, but

since there were no jobs to be found as such, he started spray painting at a local producer of farm equipment. On one occasion, he took

me to see his workplace. I still have a vivid memory of him and his

colleagues, standing in the paint both in their space suits, which were

meant to protect them from inhaling paint fumes. It probably did

9

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

so—to an extent. But I also remember my mother complaining about

how the bedsheets always had a slightly pink hue to them, due to

my father sweating out residues of the red paint from the factory at

night. This book is dedicated to the memory of my father, Knud Erik

Christensen (1930–2016), and to all the industrial workers around the

world, who are still producing the goods the rest of us use or consume

every day.11

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

Introduction

This is the story about one of the first ever factories in Europe, making cars by modern methods of mass production, including the assembly line. The factory was located in Copenhagen, Denmark, and

its name was Ford Motor Company A/S.

Not many foreign observers in general, or historians of business,

labour, or technology in particular, would associate Denmark with

any type of car industry. To Danes of the present generation, cars are

something that we import from Asia or from much larger European

countries, not least neighbouring Germany—or even from our close

cousins in Sweden. But there was in fact a time, when a rudimentary

German auto industry looked with envy upon the state of affairs in

Denmark, and when Sweden was flooded with cars from Copenhagen.

To be honest, the golden age of our car industry cannot entirely be

attributed to Danish ingenuity and resourcefulness. On the contrary,

as the name Ford Motor Company suggests, it was brought to the

country from outside, as the then-largest manufacturer of cars in the

world decided to establish an assembly plant in Denmark in 1919. The

immediate success of Ford attracted other foreign operators, most

notably General Motors and Citroën, and for a period in the interwar

years, Copenhagen was a Detroit in miniature.

Having passed through the Copenhagen South port area several

times, noticing the iconic building that once housed the Ford assembly plant, I became interested in knowing more about its history.

I was also vaguely aware that it had been the site of conflict between

Fordist principles of management and Danish trade unions.

Then I became involved in setting up an exhibition on industrial

culture at the National Museum of Denmark. I suggested that we

introduction

12

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

should exhibit a Ford Model T, assembled in Copenhagen, to represent this almost forgotten history. After some research I was able

to obtain a car for the museum, which had papers to prove beyond

reasonable doubt that it had been assembled in Denmark in 1924.

This was what prompted me to dig more deeply into the history

of Ford Motor Company A/S. As I found more and more source material, the story unfolded, expanded, and became increasingly fascinating. Sadly, the remains of the Copenhagen Ford plant have since

been demolished, despite attempts to have it listed as an industrial

landmark. The National Museum has abandoned its commitment to

industrial heritage and removed the Danish Ford T from its exhibitions. But at least the history of the company, which brought massproduced automobiles to Denmark, the people who assembled them,

and the impact it made may now be read on the following pages.

As the subtitle implies, this is a book not just about the Danish Ford

factory, but also about the transformation of Fordism from Detroit to

Denmark. It has the ambition of bringing the Danish experience into

the international history of Fordism, and of using it as a case for better understanding that history. For that, and in order to be able to see

the changes that took place over time and space, it starts out with a

chapter on the historical creation of Fordism, starting with Detroit in

the early 20th century. In this chapter, I also present my understanding of Fordism as made up of three aspects: as a form of production,

as a regime of industrial relations between workers and management,

and finally as a social vision.

The following five chapters, which form the main part of the book,

present the history of Ford Motor Company A/S. To help the reader

getting an overview of the narrative, it has been broken up into five

chronological periods. Within each period, it is structured under five

recurring themes: Production, Markets and models, Management, Industrial relations, and Presence. The reasons for choosing these

themes and what they imply will be explained in more detail at the

end of the first chapter.

Fordism may be seen as a special case of Americanism and its transfer to Europe as a form of Americanisation. In public debate, Americanism has often been understood as a one-way process, in which

between denmark and detroit

13

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

American cultural, political, or economic power has simply been conquering other nations. But this simplistic picture has been challenged

by research. Today, according to the prevailing notion, it is an active

process, in which the nations, cultures, and economies being Americanised play an active role themselves, ranging from resistance to

embrace—and that which is transferred from America to the receiving nations is also transformed, as part of this active process.1

It is this process I refer to as the transformation of Fordism. Through

the empirical narrative of the history of Ford Motor Company A/S,

this process may be traced through time. Consequently, a prevailing

theme throughout the narrative is how the orders, expectations, and

impulses coming from Detroit were implemented, adapted, or ignored

in Copenhagen.

The last part of the book ties together a theoretical understanding

of Fordism with the previous narrative of the history of Ford in Denmark and tries to point out what we might learn from this narrative

about the actual transformation of Fordism from its origin in Detroit

in the early 20th century to post-war Europe.

When discussing this last topic, special attention will be given to

the Social Democratic Party and the labour movement. The reason

for this is that the social democrats became the leading political

party and rose to power during the period in which Ford established

itself in Denmark. At the same time, the party started on the political path which would lead to the welfare state. During the post-war

years, when Denmark became firmly included in the “western camp”,

the social democrats were also a leading political force. The Social

Democratic Party was heading the government in roughly 35 out

of the 47 years covered in this book. It is therefore of interest, if any

influence or inspiration from Fordism can be identified in relation

to this party.

My own academic background is in labour history, especially that

of labour unions in industry, which has gradually expanded over the

years, into the social and cultural history of industrial society in general. To write the story of Ford Motor Company A/S, I have had to

reach out into disciplines with which I am not totally unfamiliar but

in no way an expert, most notably business history and economic hisintroduction

14

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

tory. Grazing beyond one’s usual academic pastures may enhance the

risk of misstatement, but compared to the safe but tedious results of

confining oneself to the same, small plot, it is a risk worth taking.

In a study like this, many topics arise, and many questions pose

themselves, which may not always be answered. Just one example:

a systematic comparison between Ford Motor Company A/S and

one or more of Ford’s other European assembly plants, especially

in regard to management and industrial relations, would have been

beneficial to our understanding of what was specific and what was

general to the history of Ford in Denmark. Unfortunately, this would

require work beyond the resources available. I have tried to strike

a balance, which includes both relevant theoretical discussion of

Fordism as well as parts of its European context, where it is needed

most—but still allows for a detailed and vivid presentation of the

actual history of Ford Motor Company A/S.

The text is generally British English. But several terms related to

cars, such as specific parts and types are different in American English.

And since the American terms of course are used by Ford, the same

will be the case in this book to avoid confusion. For example, the

cover of the engine is called the hood (not the bonnet), while conversely the part that can be raised to cover an open body is called the

top (not the hood). Chassis can refer to the frame on which a car

is built, as well as a complete car just without a body mounted. Similarly, a load-carrying motor vehicle is called a truck. If necessary, the

meaning is specified in the text.

Inside the auto-industry, cars that are delivered for sales as preassembled, as opposed to being assembled locally, are known as

built-ups. Pre-assembled and built-up are used interchangeably in the

following.

Ford Motor Company A/S is always a reference to the Danish company. When only the name Ford or Ford Motor Company is used, it

might be a reference to the global enterprise or to a specific, national

subsidiary. If the meaning is not clear from the context, national subsidiaries will be identified with the name or abbreviation of the country in question, for instance Ford UK.

In colloquial Danish, the term for union might be used for both

local branches as well as national associations. To avoid misunderbetween denmark and detroit

15

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

standings, the term association is used in the following, when referring specifically to the national level of union organisations. An

agreement is to be understood as the written result of collective

bargaining between unions and employers, roughly similar to what

is sometimes called a union contract in English. A shop steward is

a union representative, elected by and among workers at shop floor

level. A leading shop steward is the elected spokesperson of all workers at an enterprise. Further details about concepts and institutions

in the Danish system of industrial relations are given at relevant

points in the text.

The distinction between skilled and unskilled labour is important

for understanding the conflicts caused by the transformation of Fordist industrial relations into a Danish context. In the following, a craftsman means a skilled worker, who has completed an apprenticeship,

while a workman is a worker with no formal training.

Dates are generally given in the order of day, month, and year, except in quotations where the original format is retained. Danish quotations have been translated by the author, unless otherwise noted.

Henry Ford had

no ideas on mass production

Charles Sorensen

17

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

The Creation of Fordism

What is Fordism? Unfortunately, there is no simple answer to that. In

contemporary public debate, Fordism is often used to label a certain

period in the history of the western economy, a period characterised

by mass production, high productivity, and a social compromise between organised labour and capital, as well as a period of rising consumption and the establishment of some variation of welfare state in

large parts of Western Europe. Fordism in this sense is an era of the

post-war period, reaching its apex in the 1950s and 1960s, before it

was challenged and maybe even defeated by other regimes of accumulation by the end of the 20th century.

But we may trace the historic roots of Fordism to a time long

before that: the very beginning of the 20th century. It was then that

Henry Ford entered onto a path towards a novel form of industrial

mass production, based on the assembly line, taking place in a factory

regime where intensive labour and strict discipline are remunerated

by high wages. Fordism in this sense reached its apex around 1920,

when Ford Motor Company had become the world’s largest manufacturer of mass-produced automobiles. This was also the Fordism

that was popularised, envied, but also criticised by many in Europe

during the period between the two world wars.

Not only does the conceptual understanding of Fordism, prevalent

today, focuses on a period several decades later than that in which

Fordism came into being as an empirical reality. In fact, a strict interpretation of contemporary concepts will also lead to the paradoxical

conclusion that what Henry Ford practised in Detroit in the 1920s was

not really Fordism, the most obvious out of several reasons being that

there was no welfare state in the USA in the 1920s and certainly no

organised labour at Ford Motor Company in Detroit.

the creation of fordism

18

This page is protected by copyright and may not be redistributed

Fordism Made in Detroit

The historical development of Fordism is inseparably bound to the

creation and success of the Ford Model T. Charles Sorensen was a

Danish immigrant who started working for Ford in Detroit as a pattern maker and ended up being vice president of the company.

Sorensen was deeply involved in the design and development of the

Model T, and he would later claim that:

Henry Ford had no ideas on mass production. He wanted to

build a lot of autos. He was determined but, like everyone else

at that time, he didn’t know how. In later years he was glorified

as the originator of the mass production idea. Far from it; he

just grew into it, like the rest of us.1

While it might not be quite fair to say about a man who worked with

Fords determination that he “just grew into it”, Sorensen’s claim is to

the point in the sense that the development of the Fordist Model of

production did not follow a previously thought-out masterplan. It

was a step-by-step process, based to a great extent on trial and error.2

Since the marketing of the first commercially available petroldriven automobile by Carl Benz in 1886, most cars had been produced

in limited quantities at high prices. Around the turn of the century

serial production had gradually been introduced, especially in the

USA, but the car was still considered a luxury product. It was Henry

Ford’s vision to make “a motor car for the great multitude”, built by

“the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise” and, consequently, “so low in price that no man making a good salary will be

unable to own one”.3

Ford Motor Company had already introduced serial production

with the Model N, the predecessor to the Model T. For the Model N,

Ford had applied the use of special purpose machines, jigs, and fixtures, making it possible to produce completely interchangeable

parts, and thereby eliminating the time-consuming process of fitting

by hand during final assembly. Already in the period of the Model N,

Ford Motor Company proudly declared: “We are making 40,000

between denmark and detroit